ENTER OUR VIDEOS

RECEIVE OUR WORK

Enter the full collection of our

tributes to Saints on YouTube.

Be notified quietly by email of our prayers,

reflections and new videos, free of charge.

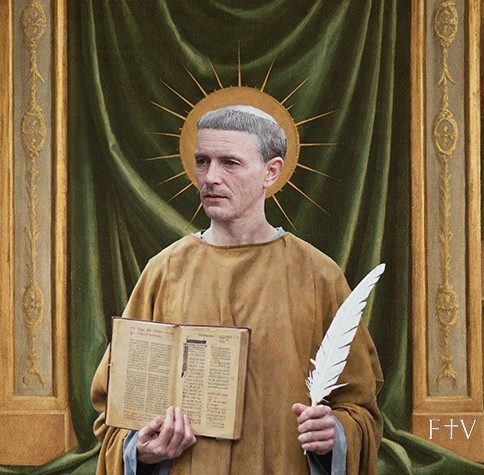

Saint Rabanus Maurus

Saint Rabanus Maurus–Patronage & Symbols

Born: Mainz region, (in what is now Germany) c. 780

Died: Winkel, near Mainz, 4 February 856

Traditional Feast Day: 4 February—Honoured for his teaching, building of monastic schools and libraries, preservation of patristic wisdom, and charitable governance during famine.

Modern Roman Calendar Feast Day: 4 February (local calendars, particularly Fulda, Mainz, Limburg, Wrocław)

Canonized: Pre-Congregation—cult attested through local and regional veneration; formally included in Roman Martyrology (2004 edition) as "Sanctus Rabanus Maurus, archiepiscopus Moguntinus"

Patron Of: Teachers, librarians, students (modern invocations); no widespread medieval patronage titles

Symbols: Open book (patristic tradition), cross-inscription or letter-grid (carmina figurata from In honorem sanctae crucis), writing stylus, Chi-Rho motif, archiepiscopal vestments

Invoked For: Wisdom in teaching, patient preservation of truth, guidance for students and scholars, perseverance in building institutions, grace to labour without despair, restoration of what has fallen into ruin

Rabanus, Hrabanus, Rhabanus Maurus, Magnentius

Modern sources sometimes claim Rabanus "knew Greek and Hebrew," but this contradicts the evidence. The claim originated in 19th-century reference works (e.g., 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica) and persists online. Modern scholarship shows Rabanus did not know Hebrew and had only rudimentary Greek (alphabet, loanwords from patristic texts).

The evidence:

The Encyclopaedia Judaica states: "Although he did not know Hebrew himself, [Rabanus] possessed a sound knowledge of Jewish biblical exegesis" through Latin intermediaries. Rabanus used a contemporary Jewish informant he calls "Hebraeus quidam moderni temporis" for Hebrew explanations, and explicitly excludes himself from "those who know the Syrian and Hebrew language." His biblical commentaries cite Greek and Hebrew terms entirely from Jerome, Isidore, Augustine, and his Jewish source—never from direct textual engagement. Unlike John Scottus Eriugena (who knew Greek and translated theological works), Rabanus never translated manuscripts or worked with original Greek or Hebrew texts.

Origin of the false claim:

Early modern biographers misinterpreted Rabanus's treatise De inventione linguarum ("On the Invention of Languages"), which lists alphabets with brief notes, as evidence of linguistic mastery. Notably, Rudolf of Fulda, Rabanus's own disciple, never mentions Greek or Hebrew knowledge in his Vita Rabani.

Conclusion:

Rabanus transmitted Greek and Hebrew knowledge through Latin intermediaries

—not through original texts—making patristic linguistic scholarship accessible to the Carolingian world and earning his title Praeceptor Germaniae ("Teacher of Germany").

Did Rabanus Maurus know Greek and Hebrew?

Biblical Commentaries

Rabanus produced extensive commentaries following the catena tradition (compiling patristic authorities): Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, Ruth, Kings, Chronicles, Judith, Esther, Proverbs, Ecclesiasticus, Wisdom, Canticles, Jeremiah, Lamentations, Ezekiel, Maccabees, Matthew, and the Pauline Epistles (including Hebrews). These were designed for preachers and teachers rather than speculative theology.

De institutione clericorum (On the Training of the Clergy, c. 819)

A manual for clerical formation addressing liturgy, sacraments, clerical discipline, and the liberal arts. The work became a standard text in Carolingian episcopal schools. Rabanus explains that clergy must be “well-nourished with the food offered to them by Holy Church” from childhood to be fit for sacred orders.

De rerum naturis / De universo (On the Nature of Things / On the Universe, 842–847)

An encyclopedic compilation in 22 books synthesizing inherited learning—natural philosophy, biblical symbolism, moral taxonomy—arranged as a reference tool for schools and preachers. Heavily dependent on Isidore of Seville’s Etymologies.

De laudibus sanctae crucis / In honorem sanctae crucis (In Praise of the Holy Cross, c. 810)

A cycle of figured poems (carmina figurata) binding text, geometry, and praise into visual theology. A ninth-century copy from Saint-Denis (845–847) shows Rabanus kneeling before a huge green cross formed of interlaced text.

Martyrologium (c. 845)

A liturgical calendar of saints designed to order and transmit the Church’s commemorative tradition for clerical use. The martyrology circulated widely and influenced later calendars.

Veni Creator Spiritus (Come, Creator Spirit)

Traditionally attributed to Rabanus. One of the most widely sung hymns in Western liturgy, used at Pentecost, ordinations, and papal conclaves. The attribution appears in medieval hymnals with sufficient consistency to be treated as early tradition.

Major Works of Rabanus Maurus

Remembering Saint Rabanus Maurus

Rabanus Maurus belongs to that class of figures whose influence is carried not by miracles or martyrdom, but by the patient construction of institutions, the correction of texts, and the formation of minds. He sits at the center of the Carolingian world because his work touched the places that shape a civilization from within: schools, libraries, liturgy, and the intellectual discipline of clergy across generations. His legacy survives in letters, teaching texts, biblical commentaries, and institutional results

—the material record of a builder rather than a performer.

The hagiographical tradition around Rabanus developed late. No contemporaneous vita survives from the ninth or tenth century. The only full medieval Vita beati Rabani Mauri is by Johannes Trithemius (1515). A brief Vita Rabani abbatis and a collection of miracle accounts (Liber Rabani de reliquiis Sanctorum) by Rudolf of Fulda (†865) appear in the Miracula sanctorum in Fuldenses ecclesias translatorum (843–847), but these focus on the relics and miracles at Fulda rather than on Rabanus’s life. Contemporary references appear in the Annales Fuldenses (MGH SS VIII), which record his appointment to Mainz (847), his charity during the 853 famine, and his death (4 February 856). His letters appear in MGH Epistolae Karolini Aevi, and he is named in Carolingian diplomas and monastic cartularies. The earliest recognizable memory-shape of Rabanus is therefore documentary and clerical, not hagiographical.

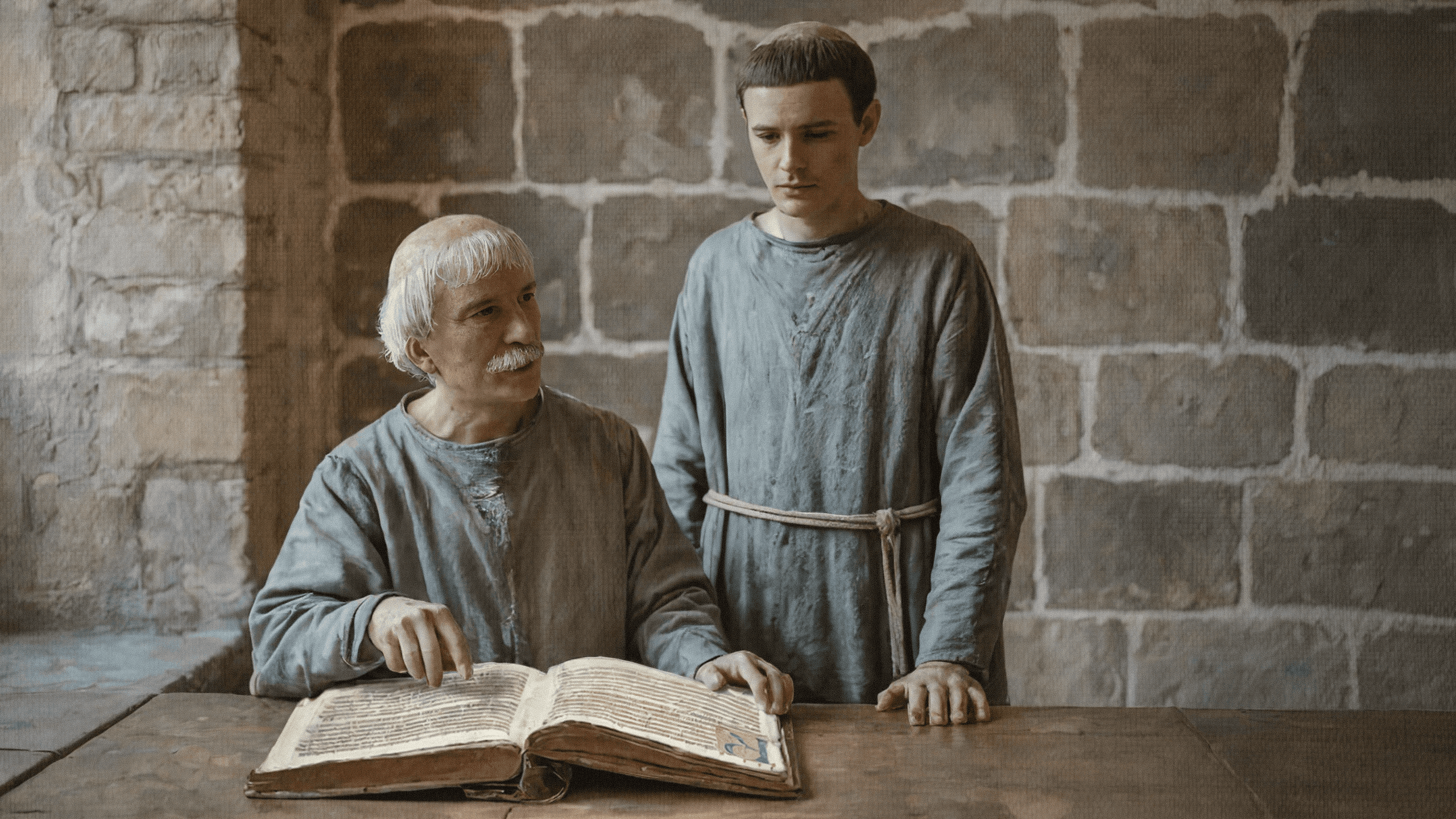

Alcuin of York with Charlemagne at Aachen—architect of the Carolingian educational reforms

that his pupil Rabanus Maurus would later build into the lasting institutional framework of medieval Christian learning.

The Carolingian Renaissance was not a return to antiquity—it was an assertion of Christian unity through education and textual discipline. Charlemagne’s reforms pressed for corrected books, clear Latin, and trained clergy. Schools were promoted across monastic and episcopal centers; psalms, chant, and grammar were treated not as optional embellishments but as instruments of imperial and spiritual unity.

This was institutional engineering on a civilizational scale.

Alcuin of York, brought from Northumbria to the Frankish court, drafted the blueprints. His pupils became the builders. Rabanus Maurus, formed at Fulda and then at Tours under Alcuin, was among the most decisive. When Rabanus wrote, he was not simply preserving texts—he was constructing an order that had not yet fully existed, shaping the intellectual inheritance of the Latin West into a usable, teachable system. His commentaries, encyclopedias, and liturgical works belong to this Carolingian effort: building the scaffold of Christendom through disciplined transmission.

The Carolingian Project: Order, Language, Discipline

Child Rabanus brought to Fulda Abbey by his father—entering the Benedictine monastery founded by Saint Boniface,

where he would be formed in monastic discipline and begin his path as Teacher of Germany.

Rabanus was born around 780 in the region of the civitas Moguntiacensis (diocese of Mainz). Later tradition describes him as of Frankish parentage, though no contemporary source names his parents. He entered the Benedictine monastery of Fulda—explicitly “in urbe Fuldensi”—as a boy, formed within its monastic school. Fulda had been founded by Saint Boniface and was a major imperial abbey in East Francia, bound to the Carolingian reform program from its origins.

Formation: York’s Discipline Transplanted to Fulda

Young Rabanus under the instruction of Alcuin of York at Tours—receiving the Northumbrian tradition of disciplined learning,

biblical commentary, and the moral vocabulary that would define his life's work.

The decisive intellectual formation came at Tours under Alcuin of York, likely between 802 and 804. Alcuin had established the palace school at Aachen and later reformed the monastery of Saint Martin at Tours, pressing for textual correction, clear Latin, and a stable clerical curriculum. At Tours, Rabanus would have encountered the Northumbrian tradition of disciplined learning, the catena method of biblical commentary, and the moral vocabulary that bound education to Christian governance. Alcuin reportedly gave him the name “Maurus,” connecting him to the tradition of Saint Maurus, disciple of Saint Benedict. This was not sentiment—it was branding, a sign of institutional continuity.

Rabanus returned to Fulda and became its scholasticus (head of the school), then deacon, priest, and eventually abbot. Under Abbot Eigil (d. 822), he served as subdeacon, deacon, and priest, then succeeded as the fifth abbot of Fulda in 822.

Rabanus’s twenty-year abbacy (822–842) was a period of visible, documented construction—both architectural and intellectual. Rudolf of Fulda’s account notes that Rabanus “applied himself to the Rule of St. Benedict” and gained a reputation as teacher and reformer. According to the same tradition, Rabanus “founded a public school in the monastery of Fulda” for the monks, strengthening an already flourishing educational center.

Fulda’s library expanded under his direction. He traveled to acquire manuscripts and pressed for copying and correction, participating in the broader Carolingian drive for textual reliability. The school produced pupils who became abbots, bishops, and teachers across Charlemagne’s empire. His students included Walafrid Strabo (later abbot of Reichenau), Otfrid of Weissenburg (author of the Old High German Evangelienbuch), and Servatus Lupus of Ferrières (noted classical scholar), each of whom is explicitly connected in the tradition to study at Fulda under Rabanus.

Abbot of Fulda (822–842): Building in Stone and Parchment

Rabanus also participated in the Carolingian culture of relic acquisition and liturgical organization. Rudolf of Fulda’s Miracula sanctorum in Fuldenses ecclesias translatorum (843–847) recounts numerous relic translations to Fulda, including those of Saints Abdon and Sennen, Nazarius, and others. Another text, the Translatio Sancti Alexandri (851), praises Rabanus’s role in translating St. Alexander’s relics to the imperial abbey. These accounts mix history and miracle-story, but they firmly link Rabanus with relic-veneration at Fulda and with the textual framing of cult memory.

Around 845, Rabanus compiled a Martyrologium—a liturgical calendar of saints intended to order and transmit the Church’s commemorative tradition for clerical use. The martyrology circulated widely and influenced later calendars. During this same period, amid the civil wars that would soon force his resignation, Rabanus compiled De procinctu romanae miliciae, an annotated abridgement of Vegetius’s De re militari adapted for Frankish warfare. The work reflects his engagement with the practical concerns of the realm, offering military-organizational advice to Lothar I’s court.

In 842, amid the civil wars following the death of Louis the Pious and the realignment of power in East Francia, Rabanus resigned the abbacy and withdrew from active governance. In the political struggle between Louis the Pious and his sons, Rabanus had supported Louis and then Lothar I. When Lothar was defeated by Louis the German in 840, Rabanus fled the monastery briefly before returning and then retiring to nearby Petersberg in 842. The political storms of the period—territorial divisions, conflicting loyalties, and the breakdown of imperial unity following the Treaty of Verdun (843)—made monastic leadership precarious. Rabanus’s retirement appears tied to these pressures rather than to personal scandal or doctrinal conflict.

In 847, Emperor Lothar’s brother Louis the German appointed Rabanus Archbishop of Mainz, succeeding Otgar. The Annales Fuldenses note: “Otgarus, Bishop of Mainz, died… in whose place Hrabanus was ordained on VI Kalendas Juli” (26 July 847). The restoration was both symbolic and strategic: a proven administrator returned to the governing spine of the imperial church.

Resignation and Reconciliation (842–847)

As archbishop, Rabanus governed one of the largest dioceses of East Francia. He attended councils, issued pastoral and disciplinary directives, and participated in the synodal life of the realm. He convened three major provincial synods during his tenure: in 847 at St. Alban’s (addressing ecclesiastical discipline with 31 canons on clerical conduct and church order); in 848 (condemning Gottschalk of Orbais’s predestination doctrine); and in 852 (defending Church rights and property against secular encroachment).

His most visible doctrinal intervention came in the predestination controversy. Rabanus opposed Gottschalk of Orbais and is directly linked to the condemnation of Gottschalk’s teaching at the Council of Mainz (1 October 848), after which Gottschalk was handed over to Hincmar of Reims for punishment. Rabanus’s posture here was not that of a speculative innovator, but of a governor defending received boundaries and ecclesial order. His anti-Gottschalk writings circulated as authoritative texts in the debate.

The Annales Fuldenses record his charity during the 853 famine: “he was at the village called Winkela… and sustained more than 300 poor daily with food.” This is not hagiographical embellishment—it is a chronicle notice of administrative fact.

Archbishop of Mainz (847–856): Pastoral Governance and Doctrinal Enforcement

Rabanus’s output is vast and methodical. His biblical commentaries follow the catena tradition—deliberately grounded in patristic inheritance rather than personal novelty. These commentaries (on Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Judith, Esther, the Gospels, the Pauline Epistles, and others) were designed for preachers and teachers, not for speculative theology. In the prologue to his commentary on Matthew, Rabanus explains his method and purpose:

The works: commentary, Doctrine, Structure

Haec scripsi… multa multorum colligens, non solum ut pauperi lectori, qui forte non habet plurimos libros, servirem, sed etiam ut his qui in multis non possunt ad intellectum sensuum a Patribus inventorum intrare, facile aditum praeberem.

(“I have written these things… summing up the explanations and suggestions of many others, not only in order to offer a service to the poor reader, who may not have many books at his disposal, but also to make it easier for those who in many things do not succeed in entering in depth into an understanding of the meanings discovered by the Fathers.”)

This was not false humility—it was deliberate submission to the tradition. Rabanus saw his task as making the Fathers accessible, not surpassing them.

He wrote De institutione clericorum (On the Training of the Clergy), a manual for the formation of clergy that addressed liturgy, sacraments, and clerical discipline. The work became a standard text in Carolingian episcopal schools. In it, Rabanus describes the purpose of clerical education from childhood:

“…qui a cunabulis suis ad cognitionem Scripturarum introducti sunt et cibis ecclesiasticis ita nutriti, ut apti ad summos sacros ordines, opportuna doctrina sufficiant…”

(“There are some who have had the good fortune to be introduced to the knowledge of Scripture from a tender age and who were so well-nourished with the food offered to them by Holy Church as to be fit for promotion, with the appropriate training, to the highest of sacred Orders.”)

For Rabanus, education was not intellectual ornament—it was spiritual formation. Learning served sanctification, not pride.

His encyclopedic compilation De rerum naturis (also transmitted as De universo) made the inherited learning of the age—natural philosophy, biblical symbolism, moral taxonomy—usable for schools and preachers. The work was designed as a reference tool, a dictionary of meanings for clerics charged with interpreting Scripture and teaching the faith. Everything was arranged for pastoral use.

He also authored De laudibus sanctae crucis (also transmitted as In honorem sanctae crucis), a cycle of figured poems (carmina figurata) composed around 810. The work binds text, geometry, and praise into disciplined visual theology. A ninth-century copy from Saint-Denis (845–847) shows Rabanus kneeling before a huge green cross formed of interlaced text.

Rabanus died on 4 February 856 at Winkel (Vinicellum) near Mainz. The Annales Fuldenses record: “Defunctus est Hrabanus archiepiscopus Moguntiacensis.” He was buried at St. Alban’s Church in Mainz.

His cult developed slowly. There was no immediate wave of pilgrimage or miracle collection. Veneration was strongest in Hesse and Mainz, where he was remembered as a teacher and reformer. Few churches are explicitly dedicated to him, though some exist in the Fulda diocese (e.g., the Rabanus-Maurus Church in Petersberg, Fulda) and in Mainz. Medieval breviaries and martyrologies in Mainz and Fulda included him in their calendars, typically listing him as “Memoriam Sancti Rabani Mauri archiep. Mogunt.” on 4 February, reflecting an early local cult.

In 1526, Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg translated Rabanus’s relics from Mainz to the church of St. Maximin in Halle (Saale) with papal approval, bringing them in solemn procession together with relics of St. Maximin. A tombstone and epitaph (recovered at Halle) mark this translation in 1547. Later diocesan tradition preserves a different account that places an attempted transfer in 1540 that ended at Aschaffenburg, after which the trace of the relics becomes uncertain. The confusion reflects the disruptions of the Reformation period.

His feast is kept on 4 February in the Roman Martyrology (2004 edition), where he is listed as “Maurus (Rabanus Maurus, O.S.B., archiep. Moguntini, anno 856).” No modern-style canonization process framed his cult; he belongs to the older Western pattern of recognized sanctity, sustained by local and regional veneration and later universal acknowledgment in martyrological tradition.

Death, Burial, and Cult Development

Rabanus is traditionally credited with composing the Pentecost sequence Veni, Creator Spiritus (“Come, Creator Spirit”), one of the most widely sung hymns in Western liturgy. The opening Latin reads:

Veni Creator Spiritus, mentes tuorum visita;

Imple superna gratia quae tu creasti pectora…

(“Come, Creator Spirit, visit the minds of your faithful; fill with grace from on high the hearts that you have fashioned…”) The attribution to Rabanus appears in medieval hymnals and breviaries with sufficient consistency to be treated as early tradition, though no autograph manuscript survives. The hymn entered the Roman Breviary and Gradual for Pentecost, and Martin Luther produced a German versification, “Komm, Gott Schöpfer, heiliger Geist,” which became a cornerstone of Lutheran hymnody.

Another hymn attributed to Rabanus is Christe, Redemptor omnium (“O Christ, Redeemer of all”), long used for the feast of All Saints. Its opening lines in Latin are:

Christe, Redemptor omnium, conserva tuos famulos,

beatae semper Virginis placatus sanctis precibus

(“O Christ, Redeemer of all, preserve thy servants, appeased by the holy prayers of the Blessed Virgin…”) Pope Urban VIII later revised the hymn for liturgical use, but the original is essentially Rabanus’s composition.

These hymns became Rabanus’s most enduring contribution to popular Christian memory. While his commentaries and encyclopedic works circulated among the learned, Veni Creator Spiritus was sung at ordinations, councils, and Pentecost celebrations across the Latin West for a thousand years. It is still sung today.

Veni Creator Spiritus and Liturgical Memory

The Fulda tradition preserves a portrait of disciplined ascetic life. Rudolf of Fulda describes Rabanus as marked by prayer, vigils, and abstinence—“oratione… vigiliis… abstinentia”—the standard markers of monastic virtue. He governed with regularity, taught with order, and lived as he instructed—by rule.

Later ages called him Praeceptor Germaniae—Teacher of Germany—not for a single doctrine, but for a body of work that ordered the world of words: psalms, saints, commentaries, calendars.

He is not remembered in miracles. He is remembered in manuscripts.

Character and Memory

Annales Fuldenses (MGH Scriptores VIII), covering 847–856.

Rudolf of Fulda, Vita Rabani abbatis and Miracula sanctorum in Fuldenses ecclesias translatorum (843–847), MGH Scriptores XV,1.

Rabanus Maurus, Opera omnia (Patrologia Latina, vols. 107–112), including Commentariorum in Matthaeum praefatio (PL 107, col. 727 D) and De institutione clericorum (PL 107, col. 419 BC).

Rabanus Maurus, letters and correspondence, MGH Epistolae Karolini Aevi V.

Translatio Sancti Alexandri (851), MGH Scriptores II.

Primary Sources

Donald A. Bullough, Alcuin: Achievement and Reputation (Leiden–Boston: Brill, 2004).

Rosamond McKitterick, The Carolingian Renaissance (Cambridge, 1994).

Pierre Riché, Écoles et enseignement dans le Haut Moyen Age (Paris, 1989).

Bernhard Blumenkranz, “Hrabanus Maurus,” Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2nd ed. (2007).

Avrom Saltman, “Rabanus Maurus and the Pseudo-Hieronymian Quaestiones Hebraicae in Libros Regum et Paralipomenon,” Harvard Theological Review 66, no. 1 (1973): 43–75.

Pope Benedict XVI, General Audience on Rabanus Maurus (3 June 2009).

Johannes Trithemius, Vita beati Rabani Mauri (1515); critical edition in Acta Sanctorum Febr. I (Antwerp 1658).

Michel Perrin, ed., In honorem sanctae crucis (Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis 100, 1997).

Catholic Encyclopedia (1913), “Blessed Maurus Magnentius Rabanus.”

Encyclopædia Britannica (1911), “Hrabanus Maurus Magnentius.”

Martyrologium Romanum (2004 edition).

Various diocesan and scholarly syntheses on Carolingian intellectual history.